Researchers, writing in the journal Buildings, have come up with a system that allows collaboration between educators and architects to create school designs suitable to the needs of the school at the time as well as in the future. This article reviews this research.

Study: Crossing Contexts: Applying a System for Collaborative Investigation of School Space to Inform Design Decisions in Contrasting Settings. Image Credit: Gold Picture/Shutterstock.com

Studies on school design, and to a varying extent the underpinning disciplines of education and architecture, show the evident disadvantages of uncritical transfer of designs and policies into buildings.

This article details the problems within and across architecture and education, along with highlighting generalized approaches undertaken in specific situations. It further puts forth a system for creating shared understandings of pedagogical and spatial needs and possibilities to inform a school design process in two contrasting cultural contexts.

Troubles with Transfer

Architecture

Knowledge transfer or the transfer of ideas is a general practice in design and architecture. However, school buildings normally mimic contemporary architecture instead of educational imaginaries, and this mostly leads to the reproduction of the industrial model of the classroom with little recognition of the importance of context for any particular school.

Pieces of evidence depict that once basic environmental comfort levels are attained, the success of a spatial design is decided by how well it accommodates the activities of the occupying school community and aligns with the values and ethos that underpin those educational practices.

Methodology

The proposed system was created to support a school community to review their school premises, taking into account the suitability of the building for their current practices along with reflecting on new possibilities for the design and better use of space.

The system put forth in the study aims to assist a review comprising of numerous individuals—students and staff—with a range of leadership, teaching, and other experience so that different views are wholly represented and can contribute to proposed solutions.

The system depends on a series of activities. The participants work with visual-spatial materials that can be employed to mediate conversations on certain aspects of their existing premises. All three activities share features with approaches that were put forth and devised for the exploration of users’ experiences of school space.

The researchers started with an exercise where each participant draws a line on a plan of the school to indicate their movements on a typical day.

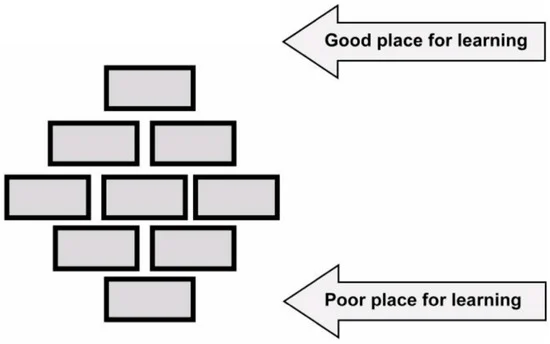

Colored stickers were used to indicate “places that work” and “places that do not work”. The participants later work in groups to ‘diamond rank’ photographs of learning environments, according to whether they represented a ‘good place for learning’ or a ‘poor place for learning' (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Instructions for “Diamond Ranking” nine images according to opinions about suitability for learning. Image Credit: Woolner and Cardellino, 2021.

The last activity asked groups to provide ideas for the development of the school premises. Using a variety of images and a plan of the school, they work together to create collages of needs and proposed solutions.

Results: Use of the System within Two Contrasting Contexts

In England

In England, the power and decision-making in the educational system are distributed through levels of management from the individual school to the national government.

In 2013, the Centre for Learning and Teaching (CfLaT) team at Newcastle University received an invitation from a newly appointed headteacher in a local primary school. The researchers carried out an initial half-day workshop and indulged in collaborative activities with school staff. The 33 participants came up with an individual map.

The second activity of diamond ranking by groups of staff came up with eight diamonds. These were later displayed for discussion between groups on what makes a better educational space.

The researchers provided a detailed report to the school on the use of space, views of the participants, and ideas for change.

In Uruguay

The education system of Uruguay is described as conventional and centralized. In 2018, the headteacher of a local private school reached out to the scientists at the Faculty of Architecture, University ORT, for advice on the design of a new building for the school.

The researchers initially held a meeting with the preschool coordinator, teachers, and teacher assistants. They then organized a walkthrough of the existing building. Observations of the use of the different spaces in the existing building were documented, and the researchers organized a half-day workshop to enable collaborative activities with educational specialists, teachers, and teacher assistants.

The 18 participants came up with a map of their movements on a typical day. The diamond ranking showed nine photographs of learning spaces which were later taken up for discussion.

At the end of the last activity, six collages were produced. The research team produced a detailed report on the use of the existing building and the views of the teachers and staff, considering its direct influence on the design of the new preschool space.

Discussion and Conclusion

The system employed works rapidly, as the activities can be completed in a single session of 2–3 hours. Another positive is that expertise in architecture and design or education is not needed.

Further, the suggested system is manageable on every occasion where a school space is proving difficult to use or a rebuilding opportunity occurs. The success of the system is solely based on the conviction that it is not educational or architectural ideas, practices, or policies that are transmitted. Rather, the focus is on generating local ideas based on local knowledge.

Journal Reference:

Woolner, P & Cardellino, P (2021) Crossing Contexts: Applying a System for Collaborative Investigation of School Space to Inform Design Decisions in Contrasting Settings. Buildings, 11, p. 496. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/11/11/496/htm

References and Further Reading

- Lawson, B (2005) How Designers Think. The Design Process Demystified, 4th ed.; Architectural Press: Abingdon, UK.

- Lawson, B (2004) Schemata, gambits and precedent: Some factors in design expertise. Design Studies, 25, pp. 443–457.doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2004.05.001.

- Rosero, V (2017) Modernity, guilty? The role of architecture in social housing. Pruitt-Igoe as a symbol. Rita. pp. 126-135.

- Nisivoccia, E., et al. (2014) La aldea Feliz. Episodios de la modernización en el Uruguay; Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Universidad de la República: Montevideo, Uruguay. p.342.

- Jamieson, P., et al. (2000) Place and Space in the Design of New Learning Environments. Higher Education Research & Development, 19, pp. 221–236. doi.org/10.1080/072943600445664.

- Abassi, N (2009) Pathways to a Better Personal and Social Life through Learning Spaces: The Role of School Design in Adolescents’ Identity Formation, in Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

- Malaguzzi, L & Zini, M (1998) Children, Spaces, Relations: Metaproject for Environment for Young Children; Ceppi, G., Zini, M., Eds; Grafiche Rebecchi Ceccarelli: Modena, Italy.

- Morgan, J (2000) Critical pedagogy: The spaces that make the difference. Culture & Society, 8, pp. 273–289. doi.org/10.1080/14681360000200099.

- Higgins, S., et al. (2005) The Impact of School Environments: A Literature Review; Design Council: London, UK.

- Whyte, J & Cardellino, P (2010) Learning by Design: Visual Practices and Organizational Transformation in Schools. Design Issues, 26, pp. 59–69. doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00005.

- Hantrais, L.(1999) Contextualization in cross-national comparative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 2, pp. 93–108. doi.org/10.1080/136455799295078.

- Alexander, R.J (2001) Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA.

- May, J. A (2014) History of Australian Schooling. The History of Education Review, 43, pp. 260–262. doi.org/10.1080/14443058.2014.996956.

- . Chisholm, L & Leyendecker, R (2008) Curriculum reform in post-1990s sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 28, pp. 195–205. doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.04.003.

- Khormi, S & Woolner, P (2019) Development of Saudi Mathematics Curriculum between Hope and Reality. International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 5, pp. 26–36.

- Alexander, R E (2011) Evidence, rhetoric and collateral damage: the problematic pursuit of ‘world class’ standards. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41, pp. 265–286. doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2011.607153.

- Auld, E & Morris, P (2014) Comparative education, the ‘New Paradigm’ and policy borrowing: constructing knowledge for educational reform. Comparative Education, 50, pp. 129–155. doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.826497.

- Clapham, A & Vickers, R (2018) Neither a borrower nor a lender be: exploring ‘teaching for mastery’ policy borrowing. Oxford Review of Education, 44, pp. 787–805. doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1450745.

- Uduku, O (2017) The Nigerian ‘Unity Schools’ project: A UNESCO-IDA school building programme in Africa. In Designing Schools: Space, Place and Pedagogy; Darian, S., Willis, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017;

- Wood, A (2020) Built policy: school-building and architecture as policy instrument. Journal of Education Policy, 35, pp. 465–484. doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1578901.

- Sanoff, H (1996) Designing a Responsive School: Benefits of a Participatory Process. 53, pp. 18–22.

- Gislason, N (2015) The Open Plan High School: Educational Motivations and Challenges.

- Carvalho, L & Yeoman, P (2018) Framing learning entanglement in innovative learning spaces: Connecting theory, design and practice. British Education Research Journal, 44, pp. 1120–1137. doi.org/10.1002/berj.3483.

- Blackmore, J., et al. (2011) Research into the Connection Between Built Learning Spaces and Student Outcomes; Education Policy and Research Division, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development: Melbourne, Australia.

- Gislason, N (2018) The Whole School: Planning and Evaluating Innovative Middle and Secondary Schools. In School Space and Its Occupation: Conceptualizing and Evaluating Innovative Learning Environments; Alterator, S., Deed, C., Eds; Brill/Sense: Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Sigurðardóttir, A K & Hjartarson, T (2016) The Idea and Reality of an Innovative School: From Inventive Design to Established Practice in a New School Building. Improving Schools, 19, pp. 62–79. doi.org/10.1177/1365480215612173.

- Uline, C L (2000) Decent Facilities and Learning: Thirman A. Milner Elementary School and Beyond. Teachers College Record, 102, pp. 442–460. doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00061.

- Cardellino, P & Woolner, P (2020) Designing for transformation – a case study of open learning spaces and educational change. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 28, pp. 383–402. doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1649297.

- Woolner, P., et al. (2014) A school tries to change: How leaders and teachers understand changes to space and practices in a UK secondary school. Improving Schools, 17, pp. 148–162. doi.org/10.1177/1365480214537931.

- Parnell, R (2015) Co-creative Adventures in School Design. In School Design Together; Woolner, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, pp. 167–183.

- Graue, E., et al. (2007) The Wisdom of Class-Size Reduction. American Educational Research Journal, 44, pp. 670–700. doi.org/10.3102/0002831207306755.

- Imms, W (2018) Innovative Learning Spaces: Catalysts/Agents for Change, or ‘Just Another Fad’? In School Space and Its Occupation: Conceptualising and Evaluating Innovative Learning Environments; Deed, S. A. C., Ed.; Brill/Sense: Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Lackney, J (2008) Teacher Environmental Competence in Elementary School Environments. Children, Youth and Environments, 18, pp. 133–159.

- . Parnell, R (2008) School design: opportunities through collaboration. CoDesign, 4, pp. 211-224. doi.org/10.1080/15710880802524904.

- Mulcahy, D., et al. (2015) Learning Spaces and Pedagogic Change: Envisioned, Enacted and Experienced. Pedagogy Culture and Society, 23, pp. 575–595. doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1055128.

- Saltmarsh, S., et al. (2015) Putting “structure within the space”: spatially un/responsive pedagogic practices in open-plan learning environments. Educational Review, 67, pp. 315–327. doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2014.924482.

- Allen, L., et al. (2009) ‘Snapped’: Researching the sexual cultures of schools using visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22, pp. 549–561. doi.org/10.1080/09518390903051523.

- Darbyshire, P (2005) Multiple methods in qualitative research with children: more insight or just more? Qualitative Research, 5, pp. 417–436. doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056921.

- Harper, D (2002) Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17, pp. 13–26. doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Woolner, P., et al. (2010) Pictures are necessary but not sufficient: Using a range of visual methods to engage users about school design. Learning Environments Research, 13, pp. 1–22. doi.org/10.1007/s10984-009-9067-6.

- Niemi, R. L. M., et al. (2015) Pupils’ perspectives on the lived pedagogy of the classroom. Education Review, 43, pp. 68–99. doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.859716.

- . Prosser, J (2007) Visual methods and the visual culture of schools. Visual Studies, 22, pp. 13–30. doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.859716.

- Halpin, D (2007) Utopian Spaces of “Robust Hope”: The architecture and nature of progressive learning environments. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 35, pp. 243–255. doi.org/10.1080/13598660701447205.

- Wilkinson, C., et al. (2021) Using methods across generations: researcher reflections from a research project involving young people and their parents. Children’s Geographies. doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1951168.

- Ball, S J (2017) The Education Debate, 3rd ed.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK.

- Saint, A (1987) Towards a Social Architecture; Bath Press: Avon, UK.

- ANEP (1995) Ordenanza 14. Normas de Habilitación de Establecimientos Privados de Educación; Administración Nacional de Educación Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 1995.

- French, R., et al. (2019) Case studies on the transition from traditional classrooms to innovative learning environments: Emerging strategies for success. Improving Schools, 23, pp. 1–15. doi.org/10.1177/1365480219894408.

- Thomson, P & Hall, C (2017) Place-Based Methods for Researching Schools; Bloomsbury: London, UK.