Building anything in or near the ocean comes with serious challenges. Saltwater, constant wave action, and changing environmental conditions wear down even the toughest materials over time. That’s why choosing the right materials for marine structures isn’t just about strength. It’s about how well they hold up after years of exposure.

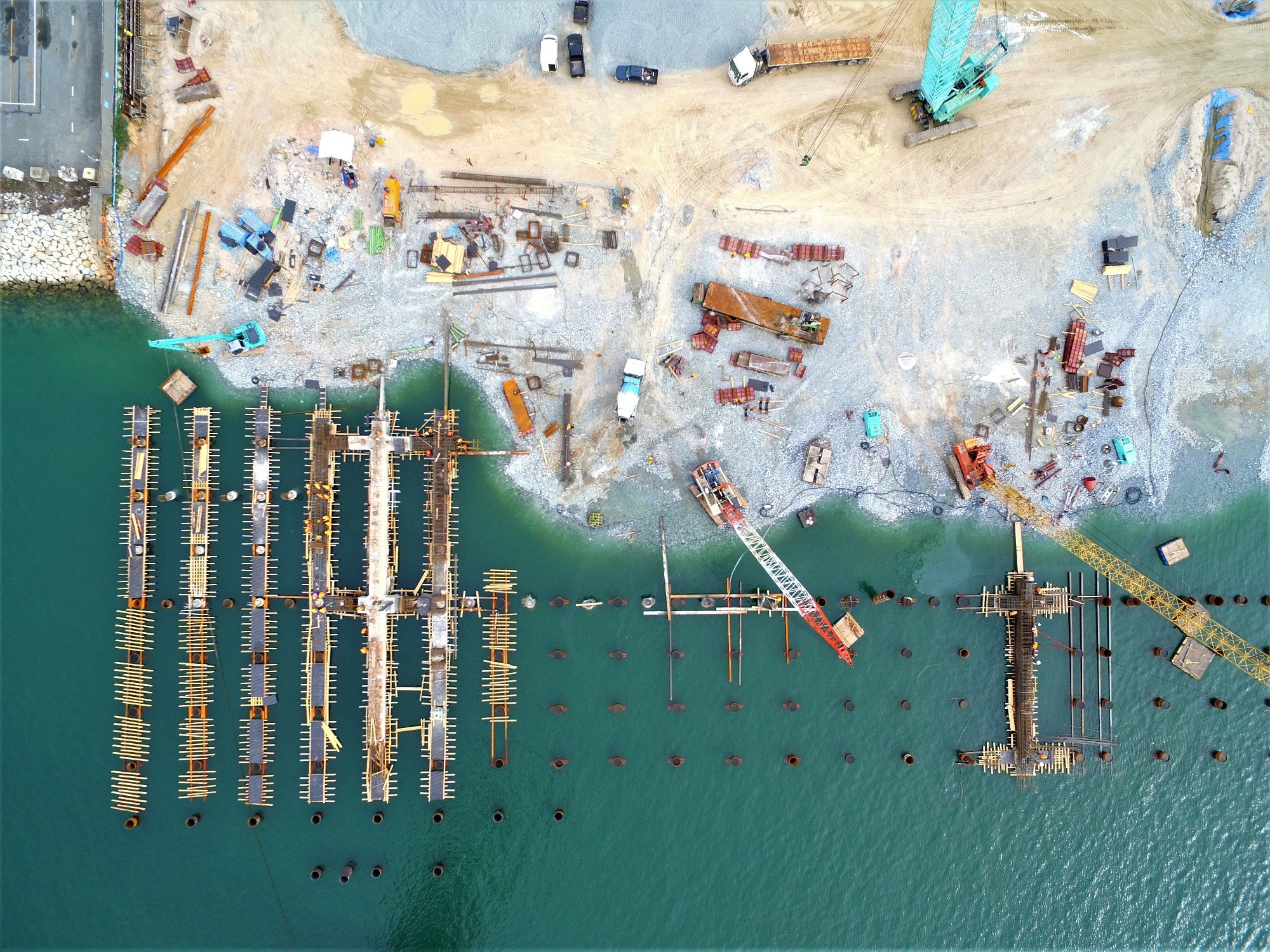

Image Credit: Phuchong.D/Shutterstock.com

In this article, we’ll look at the materials most commonly used in marine construction today, how they break down in harsh environments, and what engineers are doing to protect them.

Want all the details? Grab your free PDF here!

What Marine Environments Do to Materials

Building near or in the ocean means dealing with one big problem: everything out there wants to break your structure down.

Saltwater is full of chloride, which speeds up corrosion. Then you’ve got waves constantly hitting surfaces, parts drying out and getting wet again, and marine life clinging onto anything it can. All of this wears away at materials over time, causing cracking, fatigue, and corrosion. If that’s not accounted for early in the design, things start to fail a lot sooner than expected.1,2

And not every part of a structure is exposed to the same conditions. Something just below the surface will behave differently than a section getting splashed all day. Each zone needs its own solution, whether that be different materials or protective systems, depending on what it’s facing.

On top of all that, climate change is making the job harder. Warmer oceans, shifting pH levels, and stronger storms are changing how materials perform in the long run. This evolving landscape spurs interest in advanced concretes, composites, and coatings designed to maintain integrity in more aggressive conditions.2,3

Traditional Structural Materials

Most marine structures still rely on familiar materials, and steel sits at the center of that lineup. It’s used for piles, platforms, jackets, and decks largely because engineers understand its behavior well and know how to fabricate and install it efficiently. Structurally, it does the job. The problem starts once it’s exposed to seawater.

In marine environments, unprotected steel corrodes quickly. Chloride ions in seawater accelerate electrochemical reactions, and over time, that corrosion eats away at both strength and reliability. Because of this, steel is rarely used on its own. Instead, it’s paired with protection systems designed to slow that damage down.

That protection usually comes in the form of coatings and cathodic protection. Organic coatings act as the first barrier, while sacrificial anodes or impressed current systems help control the electrochemical processes that cause corrosion. Together, these systems extend service life, but only if they’re properly designed and maintained. In practice, material choice and protection strategy are tightly linked; you can’t think about one without the other.1,2

Concrete plays a similar role in marine construction, especially for quay walls, caissons, and offshore foundations. On the surface, concrete handles seawater fairly well. The real vulnerability sits inside the structure, where steel reinforcement is exposed to chlorides that migrate through the concrete over time. This is especially problematic in tidal and splash zones, where repeated wetting and drying speed up chloride ingress.

To slow that process, engineers focus on mix design, sufficient cover depth, and controlling cracking. When those factors are well managed, concrete structures can last for decades. But many older marine assets tell a different story. In a lot of cases, environmental exposure was underestimated during design, or construction quality didn’t meet what the conditions actually demanded. The result is reduced durability and earlier-than-expected repairs.3

Advanced Cementitious Materials

While traditional concrete is still widely used, newer cement-based materials are stepping in to solve some of its biggest weaknesses, particularly when it comes to durability in marine environments.

One of the most promising options is geopolymer concrete.

Unlike Portland cement, it’s made using industrial byproducts like fly ash or slag, activated by alkaline solutions. The result is a binder that’s more resistant to chloride penetration and has a much lower carbon footprint. For marine structures, that means better long-term performance in corrosive conditions and a smaller environmental impact.3

Another class of materials gaining attention is engineered cementitious composites (ECCs). These use tightly packed fibers to control how cracks form. Instead of wide, damaging cracks, ECCs develop very fine ones, which dramatically slows the movement of water and chlorides through the concrete. In marine environments, that kind of crack control can delay the onset of steel corrosion by years.

Similarly, fiber-reinforced concrete (which includes synthetic or natural fibers) improves toughness and resistance to cracking from impact or fatigue. It’s especially useful in repair work, where fiber-reinforced overlays can help restore damaged concrete, improve bond with existing materials, and protect the reinforcing steel by strengthening the cover zone.

There’s also growing interest in bio-based solutions, like using bacteria to produce calcite that fills microcracks. The idea is to create concrete that can "self-heal" over time, reducing the need for maintenance in difficult-to-access offshore locations.3

Metals Beyond Carbon Steel

Carbon steel might be the workhorse of marine construction, but it's not the only option when corrosion resistance becomes a priority.

Stainless steel, for example, offers much better protection against pitting and crevice corrosion in salty environments. It’s often used in reinforcement or exposed structural elements in coastal zones where failure isn't an option. The upfront cost is higher, but over time, lower maintenance and longer service life can make it a better investment.3

Another approach is using hybrid reinforcement systems. These combine traditional carbon steel with materials like carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) bars or wraps. The idea is to take advantage of each material’s strengths: steel for structural performance, CFRP for corrosion resistance, and fatigue durability. Used together, they can extend the life of structures by sharing the load and slowing down degradation.3

Beyond reinforcement, other metals like aluminum and magnesium alloys show up in marine construction for their lightweight and corrosion-resistant properties. Aluminum is especially common in components where weight matters, and its corrosion resistance can be boosted further through anodizing. Magnesium alloys are even lighter, but more prone to corrosion, so they rely on advanced surface treatments.

One treatment that’s showing promise is plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO), which creates a ceramic-like coating on magnesium. When these coatings are sealed properly, they offer significantly better protection, making magnesium a more viable option in marine settings.3,4

Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites

Fiber-reinforced polymer composites are gaining popularity in marine applications due to their high strength-to-weight ratios and resistance to electrochemical corrosion.

These composites are used in everything from hulls and decks to superstructures. Their main appeal? They don’t corrode as metals do, and they offer excellent strength-to-weight ratios. For many smaller vessels or secondary structures, glass fiber composites are the go-to. They strike a good balance between cost and performance, which is why they’ve become so common.5

When stiffness and fatigue resistance matter more, such as in high-performance boats or structural components exposed to constant loading, carbon fiber composites take the lead. They’re more expensive, but the added strength and longevity often make it worth it.

Then there are hybrid composites, which blend different types of fibers (like glass and carbon) to get the best of both worlds. These are especially useful when structures have to deal with complex or changing loads, like wave impacts or turbulent flow.

Sustainability is also part of the picture. Researchers are experimenting with plant-based fibers and bio-based resins to create more environmentally friendly composites. These materials are still being tested for long-term durability in marine environments, but they could offer a way to reduce environmental impact without sacrificing performance.6,7

Coatings and Corrosion Protection

When you’re working in or near saltwater, corrosion is just part of the job. That’s why coatings are essential. They buy time by protecting metal from exposure to water, oxygen, and chlorides. Without them, even the best structural materials won’t last long.

Most marine structures use a mix of epoxy, polyurethane, or zinc-rich coatings, depending on the exposure level. These form a physical barrier between the structure and the environment. But that barrier doesn’t last forever, especially in harsh offshore conditions, so newer coatings are being designed to do more than just sit there.

Some of the latest technology includes smart coatings that can respond to damage or pH changes. When they sense corrosion starting, they release inhibitors that slow it down. This makes them way more effective over time, especially in places that are hard to reach for maintenance.2,8

There’s also work being done with graphene and other advanced materials. These materials help improve cathodic protection systems by making it easier for electrical current to flow where it’s needed.

At the end of the day, the best results usually come from combining good coatings with a well-designed cathodic protection setup. That’s what keeps steel in service longer, especially in the kind of conditions marine infrastructure deals with daily.4

Emerging Sustainable and Circular Approaches

Sustainability is starting to show up in real material choices for marine construction, not just in reports and targets. Engineers are looking more closely at how materials are made, how long they last, and what happens to them once a structure reaches the end of its life.

One area that’s gained traction is geopolymer concrete and other low-carbon alternatives to traditional mixes. These materials can reduce emissions and, in some cases, perform better in aggressive marine conditions. The focus now is on proving that performance over time. Life-cycle assessments and durability studies are being used to check whether the environmental benefits hold up once maintenance and service life are factored in.3

There’s also growing interest in using marine plastic waste in construction materials. Some studies have looked at adding recycled plastics to concrete or composite systems as a way to reuse waste that would otherwise stay in the environment. The idea is promising, but performance still matters. Strength, durability, and long-term behavior in saltwater all need to be reliable before these materials see wider use.9

Bio-based materials, such as treated timber and seaweed-derived products, are appearing in small-scale coastal projects. They work best in specific settings, often where materials can be sourced locally. The downside is durability. Without careful detailing and protection, these materials are vulnerable to moisture and biological attack.

On the composites side, attention is shifting toward what happens after service life. New systems are being developed with recycling and recovery in mind, using bio-based resins and more efficient fiber layouts. The goal isn’t just better performance in the water, but materials that make sense across their entire lifespan.10,11

Integrated Material Selection and Future Directions

No single material solves everything in marine construction. Each part of a structure faces different conditions; some are fully submerged, others are exposed to splash, impact, or UV, and the material needs change depending on where it’s used. That’s why most designs rely on a mix. Steel for strength, concrete for mass and stability, composites for corrosion resistance, and coatings for protection.

What matters is how these materials work together. Engineers now consider the full life cycle of the structure, from its construction to its performance over decades, its ease of maintenance, and what happens when it’s eventually dismantled or replaced.3

Looking ahead, design tools are getting more advanced. Experimental data on material durability is being combined with numerical modeling and probabilistic methods to better predict how long structures will last. This makes it easier to justify using higher-performing (and often more expensive) materials up front if they reduce repair costs later on.

There’s also steady progress in coatings, corrosion science, and sustainable composites, all of which are shaping the next generation of marine infrastructure. But the goal isn’t just to build structures that last longer - it’s to build smarter. That means choosing materials based not just on cost or strength, but on how they perform over time, how they handle a changing climate, and how they fit into a more sustainable, circular economy.3,8

For early-career professionals working in coastal or offshore environments, understanding these material systems and how they interact is becoming just as important as traditional design skills. As the demands on infrastructure grow, so will the need for better decisions at every stage of a structure’s life.

References and Further Reading

- Dalmora, G. P. V. et al. (2024). Methods of corrosion prevention for steel in marine environments: A review. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces, 18, 100430. DOI:10.1016/j.rsurfi.2025.100430. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666845925000170

- Clematis, D. et al. (2022). A Critical Analysis on the Current Design Criteria for Cathodic Protection of Ships and Superyachts. Materials, 15(7). DOI:10.3390/ma15072645. https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/7/2645

- Napte, K. et al. (2025). Recent Advances in Sustainable Concrete and Steel Alternatives for Marine Infrastructure. Sustainable Marine Structures, 7(2), 107–131. DOI:10.36956/sms.v7i2.2072. https://journals.nasspublishing.com/index.php/sms/article/view/2072

- Shang, C. et al. (2024). 2D materials for marine corrosion protection: A review. APL Materials, 12, 060601. DOI:10.1063/5.0216687. https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apm/article/12/6/060601/3298433/2D-materials-for-marine-corrosion-protection-A

- Wijewickrama, L. et al. (2025). Fiber-Reinforced Composites Used in the Manufacture of Marine Decks: A Review. Polymers, 17(17), 2345. DOI:10.3390/polym17172345. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/17/17/2345

- Mohanraj, C. M. et al. (2025). Recent Progress in Fiber Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Compositesand Its Challenges-A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Natural Fibers, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2495911. DOI:10.1080/15440478.2025.2495911. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15440478.2025.2495911

- Raheem, A. et al. (2021). A Review on Hybrid Composites used for Marine Propellers. Mat. Sci. Res. India;18(1). DOI:10.13005/msri/180101. http://www.materialsciencejournal.org/vol18no1/a-review-on-hybrid-composites-used-for-marine-propellers/

- Firoozi, A. et al. (2025). Enhanced durability and environmental sustainability in marine infrastructure: Innovations in anti-corrosive coating technologies. Results in Engineering, 26, 105144. DOI:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105144. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590123025012198

- Lopes, L. et al. (2025). Marine Plastic Waste in Construction: A Systematic Review of Applications in the Built Environment. Polymers, 17(13), 1729. DOI:10.3390/polym17131729. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/17/13/1729

- Marine Biobased Building Materials: Technical Playbook. (2024). Nordic Innovation. https://www.arup.com/globalassets/downloads/insights/m/marine-biobased-building-materials.pdf

- Baley, C. et al. (2024). Sustainable polymer composite marine structures: Developments and challenges. Progress in Materials Science, 145, 101307. DOI:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101307. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0079642524000768

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.